The rise of the automobile, fit with a fossil-fuel-chugging internal combustion engine, has seen with it unsustainable behavioural changes at a wider societal scale. Acting in line with other post-industrial human technological advancements, we have gradually arrived at the “uh-oh” phase wherein policymakers are desperately attempting to undo decades of environmental damage and increasingly aware consumers are appealing for change.

So, where does this leave the state of the UK fleet? It appears as if one solution stands out amongst the crowd of emerging technologies: electric cars. They are slowly pushing competition out of the market and paving the way for their prioritisation through government subsidies and positive consumer attitudes. The UK government has placed increased taxes and charges on diesel vehicles due to their historical notoriety of being highly polluting, causing the diesel market share to plummet to 42.0% in 2018. However, this shift has partly caused average CO2 emissions for new cars to rise 2.9% from 2018 to 2019, despite being 31.2% lower than in 2000. Thanks to evolving technologies and research, diesel combustion engines have been gradually becoming less carbon emission intensive, helping the government and businesses reach emission objectives. Steadily becoming more popular with the promise of affordable, accessible, and most importantly sustainable options compared to conventional vehicles, the UK has seen a 236.4% increase in battery electric vehicles (BEV) from 2018 to 2019. With the promise of rapid growth of the electric vehicle sector, many questions have been raised by critics and consumers alike as to whether or not electric cars really are the solution to the problem, or if instead they pose new threats to our environment.

Measuring the overall emissions of electric vehicles is a difficult and complex task. We know that the greatest proportion of emissions in BEV production comes from the high amounts of electricity needed in battery manufacturing. There are multiple factors which contribute to the extent of emissions: composition of the battery (some materials are more energy intensive), source of electricity (coal, renewables etc), and the size of the battery for determining vehicle range. Lithium ion battery production, the standard used for BEVs, rare earth resources to be extracted and refined which is energy intensive in itself. Whilst most lithium ion batteries in Europe are sourced from Japan and South Korea currently which have similar energy generation sources to most of Europe, coal-powered electricity production still accounts for 25-40% of the electric grid.

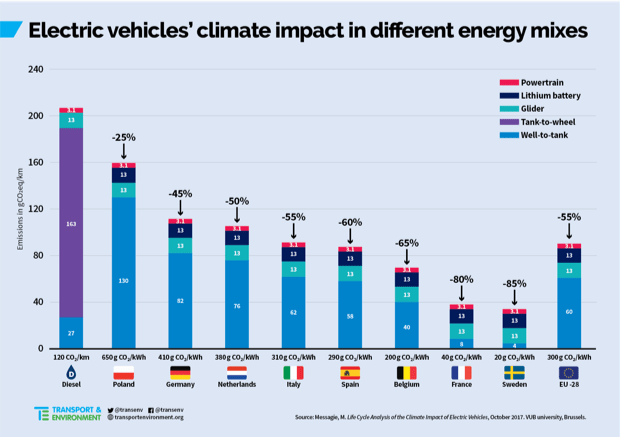

Despite the pitfalls of battery production, lithium ion battery technologies continue to advance meaning the cost of electric vehicle manufacturing is falling. With its rising popularity, this means there will be more electric vehicles accounting for fewer road emissions and travelling farther with any given unit of energy compared to conventional vehicles. Although battery production in South Korea and Japan aren’t any greener than Europe, many countries in the continent are competing with China, who use more coal, by building major battery production facilities, maintaining at least a standard of sources of energy. Crucially, BEVs in Europe generally produce 29% less carbon emissions compared to even the most efficient internal combustion engine vehicles, as shown by the figure below.

Finding the balance between the environmental gains and losses of BEVs is a vital consideration manufacturers and governments across the globe must take. Further development and research into battery recycling and second life opportunities is incredibly important in furthering the reduction of overall carbon footprint throughout the entire supply chain. Moreover, by 2030 the carbon intensity of electric grids are estimated to drop by over 30%; if this occurs globally this will result in approximately 17% lower battery manufacturing emissions. Even plug-in hybrid vehicles have lower life-cycle carbon emissions than ICE vehicles in Europe.

With all of these factors in mind, ultimately BEVs are the solution to a more environmentally friendly passenger vehicle that is accessible to the global market. The key to its success lies in grid decarbonisation, advancement of recycling and reuse technologies, and the affordability of BEVs to the average person seeking to buy a passenger vehicle.